Founders building physical products: Your $20B+ moat isn’t built by just adding software(or AI) or improving hardware.

Founders who want to make physical things face an old trap: capital intensity without defensibility.

Founders building physical products: Your $20B+ moat isn’t built by just adding software(or AI) or improving hardware.

Founders who want to make physical things face an old trap: capital intensity without defensibility.

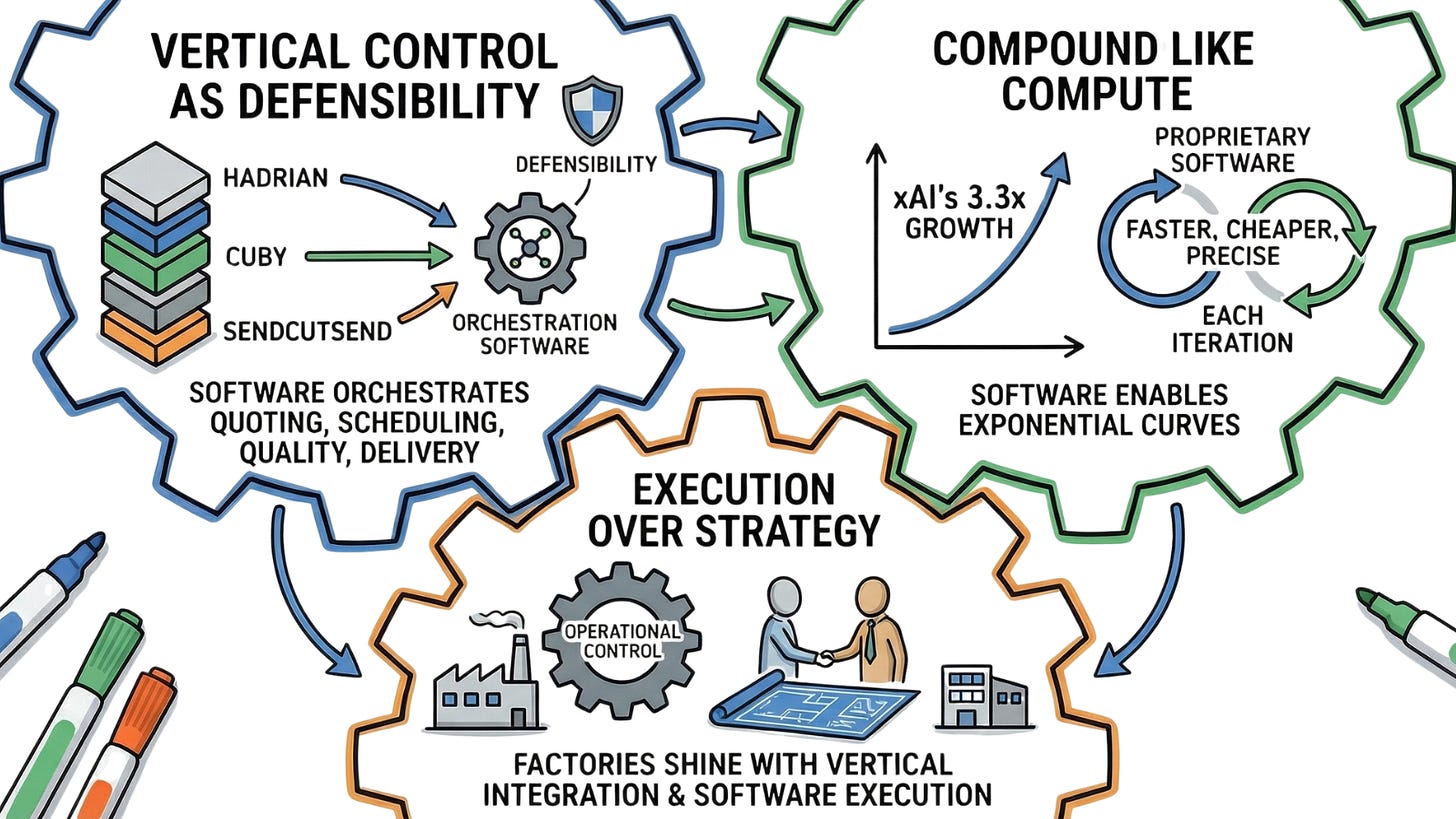

XAI, SendCutSend, Cuby, and Hadrian are rewriting the rules. Here is what they figured out.

It’s built by architecting systems where software makes every atom smarter. Miss this, and you’ll watch others compound value while you just ship more units for less profit over time.

Is Hadrian a defense contractor or a software company? This question was shoved into my brain by Andre Wegner, a friend of mine and a founder I respect in the manufacturing space. His original post (2) proposed that Hadrian’s $1.6B valuation prices it as a software platform when it is currently a capital-intensive factory, and the gap between these two business models determines whether the valuation is justified.

The question sounds simple. The answer reveals everything about where value is heading for founders who make physical things.

Marc Andreessen put it plainly: “It is flat-out easier to build companies that are just software. It just is.” (1) He called hardware startups “playing in hard mode.” Capital intensity. Supply chain drama. Higher risk. Easy to go under. He is not wrong about any of that.

But he also said something else in that same conversation about Hadrian. The opportunities in these markets are so big that “the teams that can pull it off are going to build really amazing things.”

The tension is real. And it is precisely where a hybrid model becomes interesting.

xAI grew compute 3.3x in a single year. The GPUs were necessary. But the GPUs alone were not the story. NVIDIA built the GPU’s. Software and operations innovation transformed how those physical assets performed, learned, and scaled. The hardware became a platform for compounding intelligence. Not an asset to depreciate. A system to compound.

Now look at what is happening in manufacturing.

SendCutSend (3) built instant quoting and very fast delivery directly into the customer experience without interjecting sales in the middle. Upload a file, get a price in seconds, receive precision-cut parts in a day. The lasers and waterjets are real. SCS doesn’t make the cutting equipment. They bought 14 of $1M+ machines for capacity and redundancy. The magic is in the software that makes complexity feel simple. Every job trains the system. Every quote gets faster. Every customer interaction builds data that competitors cannot replicate by buying the same machines. Where is the value multiple in that case? It’s in the system, not the hardware or the software.

Cuby (4) is building modular housing at scale. Factory production, yes. But the factory exists inside a software architecture that handles design configuration, regulatory compliance, and supply chain orchestration simultaneously. The physical structure is the output. The system intelligence is the asset.

Hadrian, from Andre’s original analysis, manufactures precision aerospace components. CNC machines, yes. But wrapped in software that learns tolerances, predicts quality issues, and compresses timelines that legacy contractors measure in months. The Pentagon needs the parts. Hadrian’s value is in how fast and how reliably those parts arrive.

Three companies. Three different industries. One pattern.

But, the media wants a simple frame. Tech company or industrial. Software margins or factory margins. Disruptor or manufacturer. Pick one. But the hybrid refuses categorization.

That refusal is precisely where the $20B+ outcomes live.

Here is what I keep asking founders who want to make things at scale:

Does your software make the factory more efficient? Does it make the atoms more valuable? Or, does your factory make the software more valuable? Do you own the software stack? Or, does someone else’s stack own you?

These questions present a fork in the road that leads to optimization. Necessary, but insufficient alone. Or, the potential for value compounding where the physical assets generate data. The data improves the software. The software increases what the assets can do. Each cycle widens the moat very quickly.

This is not about whether factories are “back” or whether Andreessen was wrong. He was right about pure-play asset ownership. Capital intensity without defensibility is a trap. Hardware is hard mode. Doing hard things is awesome!

But hybrids change the equation.

When software and atoms fuse (Fig. 1) at the architecture level, you are no longer competing on machine hours or labor costs. You are competing on institutional intelligence that deepens with every job, every customer, every iteration. That is a different game entirely.

Here is what matters most that is not said enough: this pattern is not about any single country’s industrial policy.

The conversation in America centers on reindustrialization. Bringing manufacturing home. But the deeper principle is decentralization. This started again with COVID and has been amplified by short-sighted government policy changes in the USA.

The world needs distributed manufacturing capacity, not concentrated production in any one region. Geopolitical volatility, supply chain fragility, and local market needs all point the same direction. Resilience comes from production capability that exists everywhere it is needed.

Software-enabled hybrids make decentralization possible.

A pure-play factory requires massive capital, long timelines, and deep local expertise to replicate. A hybrid, where the intelligence lives in software, can deploy new capacity faster. The machines are local. The system intelligence travels. A founder in São Paulo or Lagos or Ho Chi Minh City can build on the same architectural pattern as a founder in Elizabethtown or Detroit.

This is what reindustrialization rhetoric misses. The opportunity is not rebuilding the twentieth century in one geography. The opportunity is building the twenty-first and twenty-second century everywhere; even in Space.

The world needs founders who want to make real things. Physical things. Things that matter. Makers. But making things successfully at scale, anywhere in the world, requires understanding that the factory is not the product. The factory is a feature. The system is the product. And, that system is what must be analyzed properly to not misrepresent the value in either direction too much or too little.

Andre and Andreessen opened an important dialog. I think the answer is not binary. The answer is: what kind of hybrid are you building, and does your software make your atoms smarter over time?

So. Founders who make things, wherever you are.

What is your factory, really? And what could it become if the software was not a tool you use, but the core of what you are building?

The conversation is just starting. I think it matters; a lot.

Reference are below so that if this interests you, you can dig in and engage.

♻️️ If you found value in this post, do me a favor, share it with others that would also. Thank you for reading.

FS | I help Founders Scale. If you are a founder and feel like you’ve hit a ceiling, DM me, let’s see if we can break through together.

References

Andreessen, Marc. 2022. Rockets, Jets, and Chips: How to Modernize U.S. Manufacturing. Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), May.

https://a16z.com/rockets-jets-and-chips-how-to-modernize-u-s-manufacturing/Wegner, Andre. January 2026. LinkedIn post.

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/andrepwegner_16b-for-an-early-stage-job-shop-hadrian-share-7415692988166950912-T6pr/

Profile: https://www.linkedin.com/in/andrepwegner/He (Accidentally) Built the Amazon of Manufacturing. 2026. YouTube video, January 8. Published by The Hustle.

The Company Solving the Housing Crisis. YouTube video, December 11. Published by Spiral.